Europe's migrant influx: 'we need help but we don't know where from'

Unprecedented numbers are risking their lives to reach Europe, and local authorities in coastal communities where they land are struggling to cope. Lizzy Davies reports from Catania while photographer Massimo Sestini accompanied the Italian navy on its rescue missions earlier this month, offering a rare up-close glimpse of the men, women and children who make the dangerous trip to start a new life

African asylum seekers packed into a boat. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

With a bandana on her head and a three-month-old baby at her feet, Azeb Brahana stands in the gardens of Catania’s train station and looks a little lost. The 25-year-old Eritrean left her country in 2012, aware, she says, that the life she wanted was not possible in a country with mandatory national service. To get here, she says, she worked for a year in Sudan and endured months in a Libyan jail, where the United Nations estimates thousands of refugees and migrants are being held in deplorable conditions. It was in prison that Brahana gave birth to her son, and it is because of him that she is determined to make it, finally, to a place of safety and stability. “Somewhere I can live with my baby, happy,” she says. Somehow, though, despite all that she has.

Syrian refugees on an Italian navy ship after being rescued from a fishing vessel carrying 443 Syrian asylum seekers, 5 June. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

Syrian refugees on an Italian navy ship after being rescued from a fishing vessel carrying 443 Syrian asylum seekers, 5 June. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

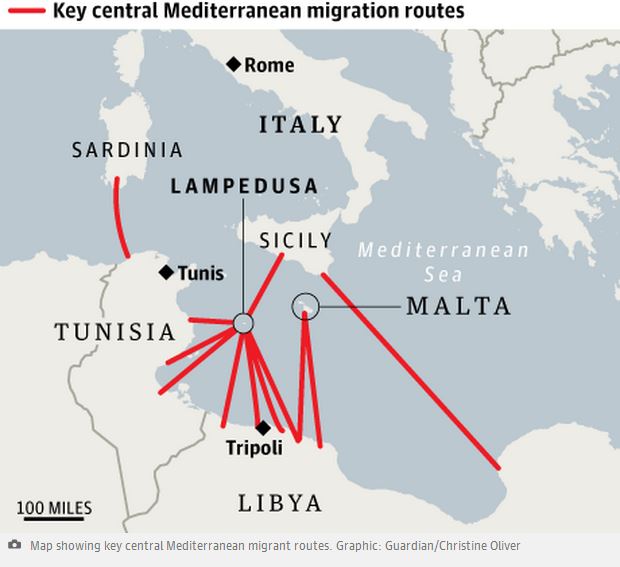

Like almost 60,000 others this year, Brahana decided to brave the Mediterranean sea in order to reach Italy, and therefore Europe. She paid people-smugglers $1,600 (£950), she says, to board a boat packed with more than 300 people. “It’s really hard with a small baby,” she says stoically of a journey that has proved deadly for thousands over the past 20 years. Her boat was intercepted by an Italian navy ship last week and all its passengers taken to safety. The question for them now is what comes next. Brahana, like many of the refugees and migrants landing in Italy, has not yet requested asylum and is not in the care of an official structure. She is waiting for the bus to Rome, where her aunt lives. And then? “I don’t know,” she admits. “I want to work. I can’t live in my country because of the government. We need help but we don’t know where from.”

According to Italian interior ministry figures given to the Guardian, 59,880 migrants and refugees have landed on the country’s coast this year – almost as many as in the whole of 2011, which holds the record. The situation is unprecedented. Sicily, which has received more than 53,000 of the new arrivals, is bearing the brunt and struggling to cope. And summer – historically the peak time for boat landings – has only just begun. “I’m very afraid that in July, August and September, the situation will grow and grow,” says Rosario Valastro, president of the Italian Red Cross in Sicily. “We have some days where we have the navy arriving in three or four different ports at the same time. My volunteers are really, really tired. I’m very afraid.”

At an EU summit this week, the Italian prime minister, Matteo Renzi, is expected to raise the issue with other leaders, urging them to make a “significant investment” in the bloc’s border control agency, Frontex. Since October, in the aftermath of two disasters in which around 400 people died at sea, the Italian navy has been carrying out a €9m-a-month (£7.2m) operation in the Mediterranean aimed at intercepting rickety migrant boats before they get into trouble. Mare Nostrum (“Our Sea”) is credited by the Italian government and NGOs on the ground with having saved countless lives. But Rome is determined that it should not continue to shoulder the burden alone. On Tuesday, Renzi told parliament: “A Europe that tells the Calabrian fisherman that he must use a certain technique to catch tuna but then turns its back when there are dead bodies in the sea cannot call itself civilised.”

African asylum seekers rescued off boats and taken aboard an Italy navy ship. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

African asylum seekers rescued off boats and taken aboard an Italy navy ship. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

All along the Sicilian coastline, in port towns better known for their beaches than for refugee crises, local authorities are begging for help – from Rome, certainly, but also from Brussels. What they need, says Lillo Firetto, mayor of Porto Empedocle, is a “supranational approach” to be taken in conjunction with the United Nations and the EU. Firetto, whose town has seen more than 8,000 arrivals this year, says the local council wants to provide a reception “worthy of its name” – but that is hard to do. “When, in the course of two days, 2,000 people arrive, and you’re forced to send them to sports halls or other makeshift structures, it’s obvious that this is not the kind of reception required,” he says.

A mother and child on a Italian navy ship after being rescued from a fishing vessel carrying 443 Syrian asylum seekers, 5 June. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

A mother and child on a Italian navy ship after being rescued from a fishing vessel carrying 443 Syrian asylum seekers, 5 June. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

Sicilian towns from Catania on the eastern coast to Palermo in the north have been transforming sports halls, churches and other buildings into ad-hoc facilities. NGOs say the system, though well-meaning, has often proved chaotic. “The problem was, there wasn’t preparation for tackling these kinds of numbers,” says Alessandra Turri, of Save the Children Italy. “Not preparing the ground and approaching it as an emergency does not allow for organisation.” People have sometimes ended up sleeping in tents, she says, because there is simply no room at the inn.

For those who do end up housed in one of the makeshift centres, the future is not much more certain. In the eastern port of Augusta, which has found itself playing a central role in the Mare Nostrum reception strategy not long after its local council was dissolved for mafia infiltration, a former primary school has been reopened to give basic food and shelter to some of the large numbers of unaccompanied minors who have come into port this year.

African asylum seekers rescued off boats and taken aboard an Italy navy ship, 8 June. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

African asylum seekers rescued off boats and taken aboard an Italy navy ship, 8 June. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

With its cracked paint, faded children's paintings, and stretched facilities, the ex-scuola Verde, as it is known, has dormitory-style bedrooms- in fact former classrooms- which can house up to 180 minors. At its busiest, however, the school is understood to have held around 267 boys. They slept on camp beds in the corridors and the changing rooms. Some of those currently resident are understood to have been living there since early May.

Many of them have stories of torture and ill-treatment on their epic journeys across Africa. “They threatened you,” says Adama Bah, 16, from Gambia, recalling his time in Libya where he says he earned the money to pay smugglers for the sea crossing to Italy. “I saw many people shot in the leg or dead.” Bah wants to be a footballer when he grows up. “That’s my dream,” he says. But here in a scruffy park in Augusta, it seems remote. “I’m not happy here because I don’t know what’s happening next.”

African asylum seekers rescued off boats and taken aboard an Italy navy ship, 8 June. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

According to Save the Children, around 5,840 unaccompanied minors have arrived on the Italian coast this year. Not all of them decide to stay in the system. At a soup kitchen opposite Catania station run by the Catholic charity Caritas, manager Valentina Calí explains that among the people who have called on its services have been “many minors who don’t want to be identified. They avoid being fingerprinted so they don’t have to request asylum in Sicily. They’re running away.”

Outside a soup kitchen opposite Catania station run by the Catholic charity Carita, Teame Habte, 20, from Eritrea, is munching on some bread with some friends, who give their ages as 15 and 16. To travel to Italy, he says, he came through Ethiopia, Sudan and Libya and was taken from the sea to Lampedusa. “My uncle lives in Rome,” he says. “I will work. I will do any work. I need to send money home because my family is very poor.”

Refugees on board a fishing vessel carrying 443 Syrian asylum seekers are rescued by the Italian navy. More than 2,000 migrants jammed in 25 boats arrived in Italy, 12 June. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

Refugees on board a fishing vessel carrying 443 Syrian asylum seekers are rescued by the Italian navy. More than 2,000 migrants jammed in 25 boats arrived in Italy, 12 June. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

NGOs on the ground say greater coordination is desperately needed in order to facilitate swift transfers to appropriate reception structures throughout Italy. “We continue to talk of an emergency about migrants … It’s not possible to talk about an “emergency” after 20 years,” says Valastro. “So we need to have a plan.” There are concerns that if the ad-hoc strategy continues and worsens through the summer, the social tensions that as yet have remained mild may be exacerbated. In Librino, a neglected part of Catania where a sports hall has been used as a temporary reception centre, the authorities moved the migrants to another hall, reportedly following concern from locals. But, surveying the scene at the Palanitta – a mass of unkempt mattresses, discarded clothes and other detritus lying between two redundant goalposts – one local is still angry. “This is what we’re left with,” he says, declining to give his name. “This is the only place where the children of this neighbourhood can come and play sport; now look at it. OK, there are going to be these boat landings. But there should be proper places for them to go. They can’t just pick a place like this and say: that one.”

African asylum seekers rescued off boats and taken aboard an Italy navy ship. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

African asylum seekers rescued off boats and taken aboard an Italy navy ship. Photograph: Massimo Sestini/eyevine

When Sicily first started to see an increase in the number of arrivals last year, the local community responded well, with donations pouring in and young people working to form a kind of network of solidarity, according to Emiliano Abramo, representative of the Sant’Egidio Christian community in Catania. “Now these things are being felt less,” he says. “In many places we have a generational clash. It seems with the economic crisis there always has to be someone to be angry with. In Augusta, this is what happened. The youngsters play football with the migrants. And their parents circulate petitions to send them away.”

LIZZY Davies

The Guardian, 25 June 2014